Article continues below

The main attraction of Castle Church in the German town of Wittenberg are the doors where Martin Luther is said to have nailed his 95 Theses, 500 years ago on 31 October 1517. The document disputed the church’s sale of ‘indulgences’ – certificates that promised salvation in the afterlife – calling into question centuries-old beliefs and practices.

Wittenberg is considered the cradle of the Reformation, and Luther its father

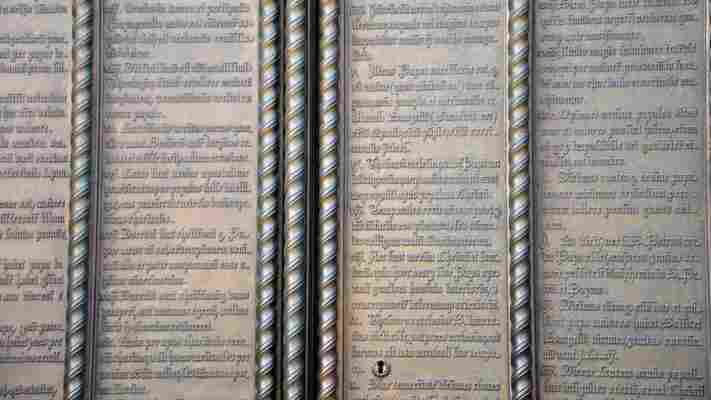

However, the doors that occupy the North Portal today are not the original wooden ones from Luther’s time, which were destroyed by a fire in 1760 during the Seven Years War. In their place stand sturdy bronze doors, embossed with the Latin words of Luther’s 95 Theses. The words are solid, fixed in place, unquestionable. But as Luther himself recognised, words have the ability to move. Just as he was moved by his reading of the Bible to question the established order, his words in turn travelled out of this small town, creating a new religious self-awareness that split the church and rocked Europe, rippling out into the world.

Perhaps that’s why I found the lofty, open space inside the church more evocative of Luther and the Reformation than those closed doors. Here, statues of Luther and his contemporaries line the nave, and it’s said that every evening after the visitors have left, the statues continue their theological discussions deep into the night. The tale reminds us that Luther was not the only figure of the Reformation; he was part of an ongoing conversation – one that continues to this day. But although other people had ideas about reforming the church, Wittenberg is still considered the cradle of the Reformation, and Luther its father.

Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses on the doors of Castle Church on 31 October 1517 (Credit: Madhvi Ramani)

You may also be interested in: • The German village that changed the war • Why people think Germans aren’t funny • The world’s first Christian country?

As I walked through Wittenberg, I wondered how such a small place could have had such a tremendous impact. The old town has not changed much since Luther’s time, especially since the Allies agreed not to bomb it because of its religious significance. The park that surrounds the old town starts at one end of Castle Church, and it only takes about 15 minutes to walk through the middle of town to Luther House, where the theologian lived for most of his life, beyond which the greenery starts again. However, it was partly because of Wittenberg’s size that Luther’s ideas were able to flourish. The high concentration of great minds in this small university town meant that people frequently bumped into each other and exchanged ideas. On my short walk, I passed the courtyard where Lucas Cranach the Elder, known as the painter of the Reformation, had his workshop and printing press, as well as the house of chief Reformation theologian Philip Melanchthon.

Moreover, Luther was able to utilise the new media tools of his time, such as woodcuts and the printing press, to spread his ideas beyond Wittenberg. John T McQuillen, assistant curator of printed books and bindings at New York’s Morgan Library & Museum explained that “Luther wrote his ideas in short, concise texts – pamphlets of eight or 16 pages – that could be quickly printed and easily distributed. Without the printing press, the Reformation would never have been the historical event that it was.”

Martin Luther essentially shaped the German language as we know it today

Often credited for creating the first media revolution, Luther quickly realised how to use language, music and images to spread his messages. He increasingly published his writings in German (rather than Latin), often with images, and his catchy, vernacular hymns helped the Reformation flourish. His musical contributions have even led to him being called the father of the protest song.

Not only did his use of everyday language help spread his ideas, but using it in religious matters was essential to Luther’s revolutionary idea that salvation could be reached through personal faith alone. Therefore, he wanted everyone to be able to read the Bible themselves. In 1534, Luther published his translation of the holy book, using vivid, simple language that would be understandable to all. To do this, he had to unite the many different German dialects to create one standardised German – essentially shaping the German language as we know it today.

Martin Luther was the father of the Reformation (Credit: Hans-Peter Merten/Getty Images)

This new emphasis on the vernacular also affected the development of other languages. Protestant missionaries from Europe and North America who went to Africa in the second half of the 19th Century believed, like Luther, that the Bible should be translated into vernacular languages. “This of course included making the language fit, ie inventing writing systems where none existed and finding terms they deemed suitable for God, devil, sin, salvation and so on,” Dr Jörg Haustein, senior lecturer in Religions in Africa at SOAS, University of London, explained. However, although the missionaries wanted to convert the Africans in a way that relied on the power of personal belief, they were also convinced of their own faith’s superiority and opposed traditional beliefs and practices. This attitude encapsulates the paradox of Luther and the Reformation, which was democratising yet authoritarian. It is also demonstrated in Luther’s stance towards the Jews. After he realised that he would not be able to convert them to his version of Christianity, he unleashed a tirade of anti-Semitic writings, arguing that Jewish synagogues, schools and homes be set on fire, their assets confiscated and that they should be used as forced labour and expelled.

On the south-east facade of Wittenberg’s town church where Luther regularly preached is a Judensau (anti-Semitic sculpture) dating back to 1305. Above the relief is an inscription with the words ‘Rabini Shem Hamphoras’ (a disrespectful corruption of the ineffable name of god in Kabbalah), which was added later and refers to a derogatory comment from Luther’s writings. His texts, such as On the Jews and Their Lies, were used extensively by the Nazis, and historians have debated the Sonderweg theory, which traces a direct path from Luther to the Nazis.

The doors of Castle Church now bear Martin Luther's 95 Theses (Credit: Madhvi Ramani)

Luther’s aim was to unite everyone under one reformed church, but his ideas had implications that went beyond what he wanted or could have imagined.

“Luther unified the German language, but his religious ideas also created divisions that are still painfully felt today. The war of words was followed by religious war,” said Dr Alexander Weber from the department of Cultures and Languages at Birkbeck College in London, referring to the religion-induced conflicts that waged through Europe between 1524 to 1648. In the place of a single church, there were now competing claims to reform. Political alliances were often formed on the basis of confessional unity, and minorities were persecuted by all confessions. This resulted in waves of migration, such as French Protestants who fled to England, Scotland, Denmark and Sweden, as well as overseas, or the English Puritans who boarded the Mayflower to North America.

Luther’s effect has been so far-reaching that it has filtered into contemporary culture. For example, Luther’s conviction and his zeal to spread his words to convince others is a forerunner of evangelism today – be it tele-evangelism or radio shows such as The Lutheran Hour, the world’s longest-running Christian outreach radio program that began broadcasting in 1930 and has more than one million listeners. In 1966, Martin Luther King echoed the act performed in Wittenberg by the man he was named after when he posted a list of demands to the door of Chicago’s City Hall.

Legends say the statues inside the Church debate theology into the night (Credit: Madhavi Ramani)

Parallels can even be drawn between Luther and American whistle-blower Edward Snowden, both of whom set their own consciences above all else and challenged the superpowers of their day by using the latest means of communication to denounce abuses of power.

The words and ideas that originated in Wittenberg spun out into the world, inspiring new words and ideas, such as those by Dostoyevsky, who explored ideas of Protestantism (which in his opinion destroyed community and was too weak to stand up to faiths such as Russian Orthodoxy) in A Writer’s Diary and The Brothers Karamazov. Nietzsche, similarly, was prompted to expand on the ideas of Luther, proclaiming, “After Goethe and Luther, there was a third step to take”. He took that third step by proclaiming the death of God, most famously associated with his work Thus Spoke Zarathustra. What started in Wittenberg has been seen to influence ideas of modern liberalism, capitalism, democracy, individualism, subjectivism, secularism and more.

In the park past Luther House, mirrored walkways have been installed to celebrate 500 years of the Reformation. As I walked along them, I saw multiple reflections of myself, as well as a fractured view of the trees and shrubs around me. This, I thought, was a good representation of Wittenberg’s impact on the world – one that recreated reality and stretched infinitely.

Places That Changed the World is a BBC Travel series looking into how a destination has made a significant impact on the entire planet.

Join over three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter and Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.