There's a well-known saying from Ralph Waldo Emerson that goes: ‘It's not the destination, it's the journey’.

That's kind of how I was feeling, standing in the middle of the Malzfabrik – an enormous art and design centre that began as a malting plant more than a century ago – in Berlin's Tempelhof neighbourhood. I'd walked 20 minutes from the closest U-Bahn station, along wide, tree-lined streets almost vacant of other pedestrians to reach these towering red-brick buildings and their main square.

It's not the destination, it's the journey

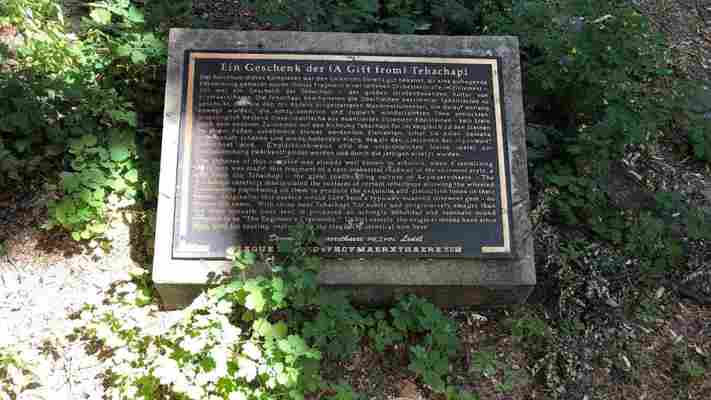

I was well off the city's typical tourist routes, and since my phone’s wi-fi kept cutting out (and the lovely woman at the Malzfabrik's front desk had never heard of the ‘Kcymaerxthaere’), I'd been wandering around this massive industrial property for over half an hour, searching for signs to a parallel universe. Finding the first one – a pillar-mounted plaque describing Sentrists , a people so self-absorbed that the centre of the universe shifts a bit when more than a few of them get together – was fairly easy, but the others (including a marker tucked within the Malzfabrik's entry garden) took a bit more sleuthing.

“You're looking for what? ” asked my friend Maria, with whom I was staying in Berlin's Kreuzberg neighbourhood, when I told her about the Kcymaerxthaere , or ‘Kcy’ – an ongoing, global, three-dimensional storytelling experience that has 140 installations, including a series of mostly square bronze plaques (or ‘markers’) and more complex ‘historic sites’, spread over six continents and 29 countries. Each installation pays tribute to a conceived ‘parallel universe’ called the Kcymaerxthaere, and shares bits of larger stories that are said to have taken place at or around corresponding locations in our own ‘linear’ world, but within an alternate dimension. It can be a heady thing to wrap your mind around.

The Malzfabrik in Berlin, Germany, houses a number of markers paying tribute to the Kcymaerxthaere, a parallel universe (Credit: Laura Kiniry)

There are markers in Perth and Las Vegas that weave in tales of the Tehachapi, the Kcymaerxthaere’s great road-building culture, while others in Singapore and Armenia revolve around stories of Eliala Mei-Ning, a woman whose voice was so beautiful it could not be concealed. Although many of the markers are stand-alone units, others (including the five found throughout Berlin's Malzfabrik) occur in clusters – and seeking them out is all part of the experience.

You may also be interested in: • The town at the centre of the world • Ancient Rome’s sinful city at the bottom of the sea • A hidden world under an Italian sewer

Kcymaerxthaere markers also exist in such far-off places as Chile’s mountainous Tierra de Fuego and along a river bank near Vilnius, Lithuania. “Plus [we have] one ready to go to the Moon,” said Eames Demetrios, the project's official ‘Geographer-at-Large’. Demetrios’ fictional story, Wartime California, about Los Angeles’ invasion and occupation of San Francisco for its water rights that he wrote in the early 1990s, was an important step in the development of this vast universe. But rather than pen a novel, the accomplished filmmaker, author and artist (as well as grandson of legendary American mid-century modern design duo Charles and Ray Eames) decided the Kcymaerxthaere would work even better as an interactive global exhibit.

“I've always felt that most movies and novels are very egocentric,” Demetrios said, “whether it's Star Wars or Pride and Prejudice, you're seeing everything through the lens of those characters. But that's not how the world really works. The people that we see in the restaurant are not there for us – they're living their own lives. So I thought, why not create a world where the world came first and the story came second.” Sporting glasses, a full head of greyish-white hair, and a boyish smile, Demetrios comes across as a forever-kid, though one who’s highly intelligent and as equally creative.

Each marker shares bits of larger Kcymaerxthaere stories that are said to have taken place at or around corresponding locations in our own ‘linear’ world (Credit: Laura Kiniry)

With permission from local property owners, Demetrios installed his first Kcymaerxthaere marker in 2003 in ‘linear’ Athens, a city in the US state of Georgia (he uses the word ‘linear’ to differentiate our world from his parallel one), though the project has really begun to flourish over the last decade. The most recent installations have been in Nepal, where Demetrios is working with the local Sherpa community on a hikeable cluster of markers about 64km from Everest; and in Portugal, which will eventually be home to a large-scale, seven-point star that stretches nearly 2,000km from marker to marker across the country. Its initial marker – a circular sky-facing plaque that sits in front of a small white church – has already been installed on Madeira, an autonomous region of Portugal off Africa’s north-west coast.

Why not create a world where the world came first and the story came second

The majority of the Kcymaerxthaere’s markers are found in out-the-way places, such as the roadside scrub of Utah's high desert, because it's not always so easy to secure the right mix of willing participants and a locale that can sustain the test of time. There are even a few markers – such as Indonesia's ‘The Life of Bala Qhova’ – that are entirely underwater. “Bala Qhova is a young man who first domesticated a creature called the water mole,” said Demetrios, “and the two-part installation [describing this part of his story] sits about 12m below the water off Bali's northern coast. You can kick your way down and get a feel for it if you snorkel, though it's much easier to view as a diver.”

But despite the sheer breadth of the project, the majority of the world’s population has no idea that the Kcymaerxthaere even exists. “I think it's partly because it’s difficult for people to stitch together the big picture because the big picture is so big,” Demetrios said.

It’s true. Stumble upon a Kcymaerxthaere marker without context and you’re likely to brush it off without a second thought. But for those familiar with Demetrios’ parallel universe (I'd first learned about the Kcy over a decade ago through a magazine article), each marker visit is like collecting a piece of the puzzle – one that literally stretches around the globe.

Eames Demetrios, the project’s ‘Geographer-at-Large’, has installed markers in 29 countries, from Chile to Nepal (Credit: Eames Demetrios)

Last October, I happened upon my first accidental Kcymaerxthaere marker: a plaque dedicated to ‘Rhyolite's District of Shadows’, which just happens to be at the spot of linear Rhyolite, one of Nevada’s best-preserved ghost towns, just east of Death Valley National Park across the California-Nevada border. It wasn't my first actual marker.

Back in 2008 I dragged my then-boyfriend through New York City’s bone-chilling December cold to the East Village, where we sought out a plaque dedicated to the ‘Sale of Manhattan’ (marking the Kcy universe spot in which Manhattan traded hands in a gambling debt, that ‘forever transformed the city’, according to the plaque) in the exterior basement stairwell of a divey neighbourhood bar (the bar has since closed and the plaque is one of a handful of Kcy markers awaiting new homes).

But the ‘District of Shadows’ was the first instance in which the Kcymaerxthaere seemingly found me. I'd been wandering among Rhyolite’s Goldwell Open Air Museum 's dozen or so outdoor sculptures – a mix of ghostly white figures made of plaster-soaked fabric contrasted with the towering Lady Desert: The Venus of Nevada , which stands like a pixelised computer image made out of cinderblocks – when there it was, a ground-embedded plaque surrounded by dirt just a few yards from the foot of a 7.3m-tall rusted bronze miner and his penguin. With the crumbling structures of the linear Rhyolite ghost town behind it, it really felt like I'd arrived in some other world.

The majority of the Kcymaerxthaere’s markers are found in out-the-way places, such as the Nevada ghost town of Rhyolite (Credit: Laura Kiniry)

Like Rhyolite's ‘District of Shadows’, most Kcymaerxthaere installations come in the form of square bronze plaques, each one adorned with a couple of hundred words describing what happened here in the Kcy universe, though Demetrios has also established some larger ‘historic sites’ that allow for more interaction.

These include the ‘Healing Palindrome’ in New Harmony, Indiana, a horseshoe-shaped ground installation made up of 19 irregularly shaped and individually placed concrete slabs. Each slab tells a part of a larger story about a biologically aquatic people who create shapes in the water to converse – a story thread that actually continues into Kcy sites in Chile, Indonesia and India.

There's also ‘Plaza de la Luna’ in Madrid, Spain: a round plaque that resembles a manhole cover and represents a gateway to the Umbrasphaere, the connection between shadows and darkness. “The darkest part of every shadow is connected to the darkest part of the next,” Demetrios said, a mind-bender that’s exactly the sort of thought-provoking imagery the Kcy – and Demetrios – often convey. “So if you’re very careful, you can use it to travel. In fact, its shape and location [about a block off the city’s Gran Vía] kind of gives you the feeling that you're actually standing at a portal,” he added.

One of the Kcymaerxthaere's most Instagrammed spots is Krblin Jihn Kabin, in Joshua Tree, California: amid the desert's yucca palms and woody plants sit this ramshackle ‘kabin’, with its crumbling walls and the remnants of a nine-point compass.

Krblin Jihn Kabin, in Joshua Tree, California, is one of Kcymaerxthaere's most Instagrammed spots (Credit: lionel derimais/Alamy)

There's an almost ethereal beauty to such a large-scale project, one that is best enjoyed in increments – much like our own linear world. However, one of Demetrios' long-term hopes is that, eventually, most of the world will be within a day's drive to a Kcymaerxthaere installation, so that you can conceivably learn about the Kcy, at school or online, and then hop in a car or bus to see it.

To help spread the word, Demetrios has put together gallery shows, lectures, a website with a map of all Kcy installations and their coordinates, an Instagram page , plaque installation ceremonies, occasional bus and walking tours, and even sing-a-longs and an annual spelling bee. He has also created a limited-edition art book called Kcymaerxthaere: The Story So Far… (Folio 1) , highlighting the project's first 138 sites, which is intended for communities where installations exist, “[So] they have something to read and refer to, and that can help them understand and relay the project better,” Demetrios said.

As for whether linear travellers will ever seek out Kcymaerxthaere sites, in the same way they embark on music pilgrimages and cross-country road trips, Demetrios said, “It will happen when it's supposed to happen.”

In the meantime, I'll have Berlin's Malzfabrik all to myself.

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter and Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.